These Singaporeans opened their doors to a homeless person. Here’s what happened

Clifford Lam (right) opened his home to Devaraj Seval Kumar in June last year. (Photos: Liew Zhi Xin/CNA)

- An informal network of Singaporeans have begun to open their homes to those in distress.

- These guests may lack a permanent place to live or have unsafe home environments.

- Hosts say the challenges include setting a time limit on the stay and managing expectations.

- While the guests and social workers address long-term housing issues, some hosts learn more about themselves.

*Names have been changed

SINGAPORE: Their parents were concerned, and some friends wondered if they were too caring, when young couple Zizie Zuzantie Mohamed Said and Lim Zhong Hao welcomed a homeless woman — seven months pregnant — to stay in their five-room flat last year.

The couple did not think too much about the little details, like whether they would wash their underwear in the same laundry load, or about the possibility of their things being stolen.

When these questions cropped up, said Zizie, they told themselves to “try to love people more than we love things”.

The couple, who are public servants, have aspired to provide a safe space for a person in need since 2018, when they encountered the homeless on a trip to London.

One individual left a deep impression — a man who held up a sign asking for money to afford a night in a shelter, recounted Zizie, 32. “We decided that one day, when we have our own house, we’d like to see how we can … host receiving individuals.”

They made good on their pledge once they got married last year. They volunteered as befrienders for outreach group Homeless Hearts of Singapore, and the call to be hosts came soon afterwards.

The Lims and four other hosts CNA Insider spoke to are part of an informal network of Singaporeans who have opened their homes to those in distress.

These guests may lack a permanent place to live, or a safe home environment owing to family violence or conflict. Their cases are usually circulated by word of mouth, for example from social workers.

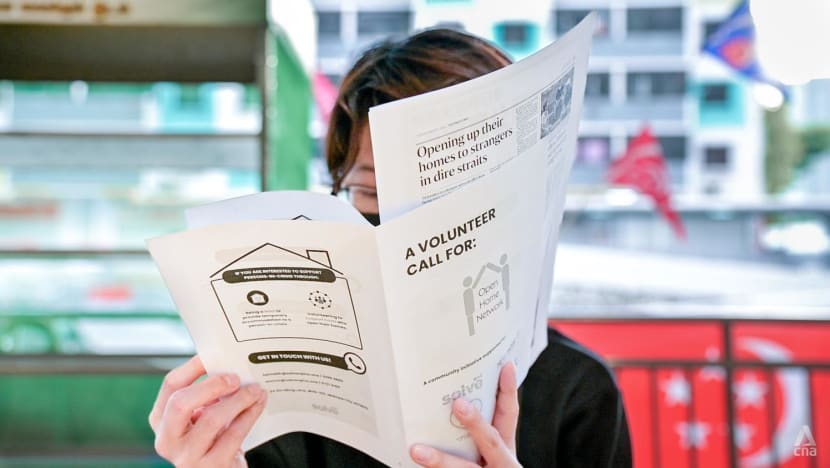

There is even a community initiative called the Open Home Network (OHN). Formed in 2020 and inspired by stories of individuals who have been hosts, it seeks to provide support and structure for those who wish to do the same.

Being a host entails opening up one’s home to provide temporary respite, “from as short as a few days to six months or even longer”, depending on the relationship between host and guest, said Emma Tang, project lead at OHN.

But opening up the sanctuary of one’s home to a stranger can come with some missteps, the hosts reflect. Those who accept the kindness, on the other hand, may find it scary at first, before gratitude surfaces.

MUCH-NEEDED RESPITE

Before Ria* and her partner, Farhan* met the Lims, they had been sleeping on a staircase landing for three months. They had moved out of their family homes into a rented room because of strained relations with their parents but were eventually evicted when they could not afford the rent.

Even though sleeping rough was tough, they were “very afraid” to return home, said Ria, 22. Their parents were against their relationship, and they feared the pregnancy would cause more disagreements, said Farhan, 24.

They sought help from a social worker to find a shelter, but most places were full, he recounted.

With a spare room available for two and a half weeks — a friend was moving in temporarily after that — the Lims said yes to hosting Ria for that time, while Farhan would move home.

When the Lims first began volunteering for the Homeless Hearts of Singapore and offered to be hosts, they were advised to look out for women and children, for whom “the streets are unsafe”. Ria fit the bill.

When Lim met the couple at the place where they were sleeping rough, Ria appeared tired, he observed. After getting to know them and connecting with their social worker, the Lims stocked up on supplies — like tom yum instant noodles, Ria’s favourite — and welcomed their guest.

It was a much-needed respite for Ria, whose pregnancy was nearing full-term. At first, she was nervous about being around strangers, but she soon felt “safe”.

“When we were homeless, I was worried about everything — showering, eating, security,” she said. “I was almost losing hope. I was also wondering if (the Lims) would be understanding, but they just took me in to care for me.”

Meanwhile, knowing Ria was safe gave Farhan room to “do whatever (he) needed”, namely, to mend his relationship with his parents and get a full-time job.

“I felt better that (Ria) had a place to stay, someone who understood the situation, and everything was taken care of,” he said.

Besides providing shelter for Ria, the Lims welcomed him to join them for dinner often, and the conversations they had motivated him to address issues with his family.

“We only told my parents of (Ria’s) pregnancy right after a long talk with Zizie and Hao,” he said. “I really needed that talk.”

WATCH: Can we help the homeless by getting Singaporeans to open their homes? (13:42)

The Lims also helped their guests’ social worker to make sure they got to important appointments, for example with a shelter and the Housing and Development Board.

“Because they’d spent time with us, we felt we were in a good position to … partner the social worker and various others in the ecosystem, to nudge them towards a more stable housing situation,” said Lim, 32.

When we see that they’re … better rested, they can make better quality decisions … They’re not so different from us.”

Ria was a “good flatmate”, the Lims recalled. She put out the laundry and washed her own dishes. Their main challenge, said Zizie, was to organise their schedules around Ria, as she was heavily pregnant and they felt responsible for her safety.

Before her stay with the Lims was up, Ria’s social worker managed to get her into A Safe Place, a temporary shelter for pregnant women.

Today, both Ria and Farhan have been reconciled with their families and are married. They also secured a rental flat with the help of their social worker.

WHEN BOUNDARIES ARE CROSSED

The Lims acknowledged that they might not be prepared for the worst.

There were times, other hosts recounted, when guests crossed boundaries. This happened to Trina* and her husband, who opened up their home in 2020 for a woman in her 30s they had heard about from the Homeless Hearts of Singapore.

They declined to elaborate on her “challenging” circumstances at the time.

But before agreeing to be hosts, they had the “same concerns most people would have”, said Trina, 28. “Theft, harassment, lack of privacy, being stuck with a difficult person and not being able to get along.”

Most of their fears came true.

While the couple had set ground rules for the stay — for example, the guest had to clean her room and bathroom — she did not abide by them.

The rug in the guest bathroom would be soaked, and there would be muddy footprints, said Trina. Reminders to her fell on deaf ears.

“This made me feel like she didn’t respect our house rules, even though she was only made to do the minimum,” said Trina.

Managing their guest’s expectations was another challenge. Trina provided her with emotional support, but that led to the expectation of constant companionship, she said. “When I wasn’t home, she’d call and ask where I was and when I’d be back.”

Being an introvert, Trina was left “exhausted”.

WHEN DO THEY LEAVE?

When they began hosting, Trina and her husband wanted the woman to feel like she was free to stay until her circumstances eased, so they did not set a cutoff date. In hindsight, that was a “mistake”, said Trina.

The woman’s situation improved over her three months staying with them, but she did not mention when she would leave, said Trina.

The woman also did not have a good relationship with her social worker, so the couple felt they had to handle the situation on their own.

“I was quite desperate to have some certainty … so I pressed her for a proper response. That was when she started shutting us off,” said Trina. “The atmosphere at home was tense and awkward.”

Eventually, their guest settled on a date to move out. She remains in touch with Trina and her husband.

While the couple have not closed the door on the possibility of being hosts in future, they have “many apprehensions”. They felt “alone in the whole endeavour” as their families were not supportive of the idea.

The prospect of not having a definite timeline for a stay is also “very daunting”, said Trina.

According to Abraham Yeo, co-founder of the Homeless Hearts of Singapore, the “greatest unhappiness” is not so much about the length of stay as the “uncertain” extensions.

His family, too, had once hosted a guest — a single mother with a toddler — beyond what he was comfortable with: A year instead of six months. Her social worker repeatedly told him of delays in securing her a flat.

“We felt like we were operating in the dark, and we had to be the ones asking the social worker what exactly is happening with the person in crisis?” recalled Yeo, 41.

“The morale of our guest was dropping, and our own morale was dropping as well, because there was so much uncertainty.”

After he raised concerns about the repeated delays, the social worker managed to secure a flat for the young mother. She eventually got married and invited the Yeos to her wedding.

When the Lims volunteered to be hosts, Yeo advised them to stick to their agreed availability for two and a half weeks, which would suggest to their guest’s social worker an “urgent” need for a solution, recalled Zizie.

Some hosts, however, have embraced the uncertainty. Clifford Lam, 39, initially agreed that his guest, Devaraj Seval Kumar, 18, would stay for three months. But it has been nearly one and a half years now.

Devaraj had been in and out of institutional homes since primary school, owing to his turbulent relationship with his parents, he told CNA Insider. He wound up in the Singapore Boys’ Home when he was 16.

After his discharge, his relationship with his divorced parents remained fraught. He went and lived with his mother and stepfather but was kicked out. Devaraj tried living with his biological father but learnt that he was in financial difficulty.

He sought help from his social worker in finding alternative accommodation. That was when he met Lam in June last year. Recently divorced and with the home to himself, Lam wanted to “bless someone” in need of a space.

Under their initial agreement, Devaraj was to return home every weekend to reconnect with his father, to try and rebuild their relationship in those three months. But things did not happen as expected.

“Because (his) dad was going through a lot of stuff at the time. Fast-forward to today (and) it’s been 15 months,” Lam, a school counsellor, said in October.

“The first extension was a bit of a shock. I was a bit disappointed … But the inner voice in my head thought, ‘What makes you think that after six months, it’s going to be good?’

“I realised that I got to think long-term.”

HELPING THE HOSTS

Stories of burnout among some community hosts were what inspired Tang’s team to start the OHN and take concerted action to help hosts and persons in crisis navigate tensions and manage risks.

What the OHN does is assign a community representative to each host, to help hosts think about their boundaries and expectations, said Tang, 25. The representatives also act as a mediator between host and guest.

If the person in crisis has no social worker, the OHN will facilitate getting one. Then there is the case manager, who helps to “track the progress” of things. The goal is for every party to “have their own advocate”.

The OHN also assesses the suitability of both the person in crisis and the host. The community group does “reference checks” to make sure there is “nothing too risky” in their background. The two parties are then matched based on their needs, preferences and availability.

Finding this “fit” is important, said Harry Tan of the Lee Kuan Yew School of Public Policy, who has researched homelessness in Singapore. “It’s important not to treat this informal structure as just a place to put persons in crisis.”

To this end, the OHN organises as many meetings as needed before the parties feel comfortable about taking the arrangement forward. The group then checks in regularly with them to address any questions or tensions that might arise, said Tang.

Opening up one’s home is still “a big stretch” for most people, she acknowledged.

“Community hosting … is contrary to the value we place on privacy,” she said. By providing structure and guidance, her OHN team hopes to give interested hosts “a little bit more comfort” in extending this hospitality.

Along with the Homeless Hearts of Singapore, they launched a pilot recruitment drive in 2020, which saw 160 families respond with interest. Eventually, about 15 families saw it through, said Tang. The applicants more inclined to sign up were empty nesters or young couples who had just got their flat.

But one does not necessarily need to open one’s home to be able to contribute to the cause, said Tang.

“What we’re hoping to do is provide different pathways for the community to care for a person in crisis … People can participate by doing advocacy (work), by volunteering to support the host.”

Volunteers can help by befriending the person in crisis or providing “operational support”, such as food and bedding, Tang added.

A MORE COHESIVE SOCIETY?

The gap in the informal structure, however, is that it “may not be equipped to deal with more complex cases”, such as persons in crisis with mental health or addiction issues, according to Tan.

“What happens if someone is depressed or suicidal? What do I do if the person who stays with me relapses?” cited Tan, who highlighted the need for experts such as counsellors to provide “wrap-around services”.

Nonetheless, if more Singaporeans open up their homes, said Tan, this informal structure could “complement the existing shelter structure”. Then shelters can focus on the more complex cases, he added.

Social workers have found that some clients are not the “best fit” for shelters, said Tang, basing this on the referrals the OHN has received. “When we provide social workers with options, it can make a big difference.

“They can get their client out of crisis mode, and they can start working on more long-term things.”

The community can also be “more agile” in terms of response time and the kind of support they can offer, said Tang. And rather than leaving the responsibility for problem-solving to social services, the community can step up, she added.

“Crisis doesn’t discriminate … rich, poor, healthy or not healthy. The question is, if crisis were to hit you, would you want to have different people you can call — that you don’t just have an institutional option but a community option?”

There is “a lot more social solidarity” emerging in communities, especially since the pandemic, observed National University of Singapore associate professor of sociology Tan Ern Ser.

“We used to think that Singaporeans are apathetic. I think it’s just not the case now. I’d say that Singaporeans are reaching out; they have a greater sense of empathy.”

But there is a post-crisis tendency for this solidarity to taper off, said Tan. And given the “heavy commitment” being a host requires, he added: “I don’t see it scaling up very rapidly, but certainly it’s a good start.”

The experts agreed that it is too soon to tell if community hosting indicates greater social cohesion, though it is “a step forward”.

WATCH: I shared my home with a stranger for 1.5 years — Housing the homeless (6:46)

“When someone opens their doors like that … it builds interpersonal relationships between people of different backgrounds, and it reduces the social distance between them,” said Harry Tan.

“Research has shown that when a person’s network becomes more diverse, it helps to build a more … understanding society.

“That’s the key foundation for building our social cohesion.”

FINDING THEIR ‘WHY’

For host Lam, his endeavour not only has allowed him to help someone in need like Devaraj, but also has been a journey of self-discovery.

“Maybe there’s this saviour mentality — that I hope when he leaves my house, something inside him changes,” said Lam. “So sometimes, maybe when things don’t really go as planned … then I wonder, is there anything I can do better?”

There are little things that bug him; for instance, when the early, light sleeper has his sleep disrupted by Devaraj’s school meetings on Zoom late at night. The dishes must also be arranged according to size on the drying rack.

He has learned that he can be “quite an ugly person”, he said. “It’s a very genuine struggle. I'm doing this out of love, but I want my space too — I want things to go my way.”

But after more than a year, he learnt to “let go of quite a number of things”, like his expectations of Devaraj, and to “live and let live” and be more “chill”.

The two now share a “comfortable relationship” and hang out for dinner at least once a week.

For Devaraj, he has gained a “father figure”. The idea of living with a stranger was “uncomfortable” at first, but he was relieved to be living away from his parents, who used to “scold him non-stop”.

“(Lam is) the first person ever to care a lot about me,” he said. “He taught me how to be an adult — (he’d say) when you have your own family, (you) must learn to do this properly, that properly.”

They even share their thoughts on relationships. “He’d tell me, like, ‘Oh, I just met this girl. She was cute.’ Then I’m like, ‘Did you get her number?’” said Devaraj.

Lam’s plan is to see Devaraj through his studies at the Institute of Technical Education until the year end.

“I think having that reason why you want to do this will see you through the difficult times and the very beautiful times,” said Lam.

“I'm hoping that … when he packs his bags and leaves this house, when he starts his own family, he remembers what he had here.

“Hopefully, that changes his story.”

Read this story in Bahasa Melayu here.